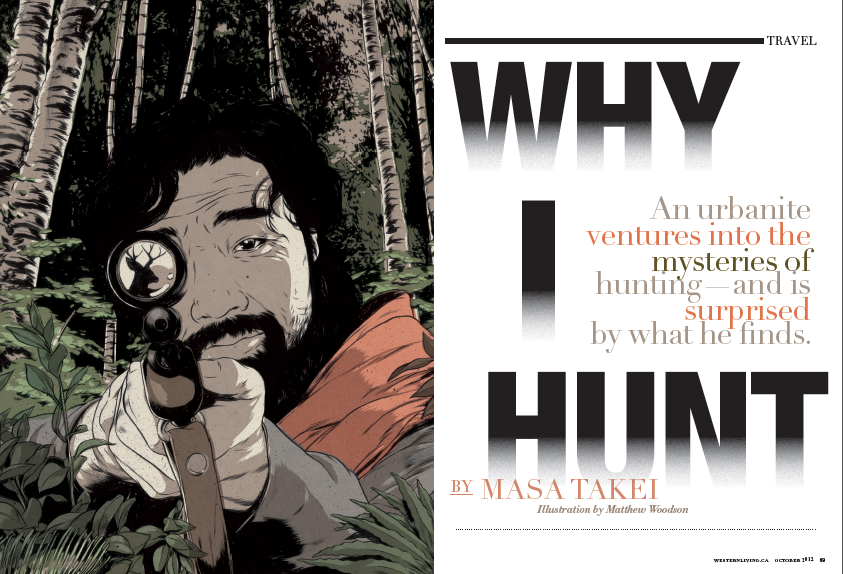

An urbanite’s journey in becoming a hunter. Finalist for a Western Magazine Award.

Two autumns ago I stood on the edge of a clearcut in the Cariboo Chilcotin. It was mid-morning and the sun was just warming over the semi-arid landscape. A spike buck muley lay in the brush at my feet, its eyes glassed over, an entry wound the size of a dime on its chest. A solid shot through the engine room. The deer had bounded fifteen yards into the tree line then dropped.

My rifle—the proverbial smoking gun—hung heavy in my hands. I keyed the mike on my radio and told my hunting partner where to find me, feeling as if I was turning myself in.

This was the moment I’d spent much time and effort at which to arrive. From a standing start, I’d spent two years becoming a hunter. And after all that, finally finding what I’d sought, I had to remember again why I’d sought it out at all.

If you’d told me five years ago that I’d become a hunter, I would have turned up a lip. I was a 30-something urbanite of the Vancouver persuasion, complete with standard issue, left-leaning values. I wore Arc’teryx and drove a Subaru.

Hunters, to me, were empty-Bud-can-tossing rednecks or semi-flaccid rich businessmen (a camo class at both ends of the economic spectrum). They killed for fun or ego gratification. They killed for “sport.”

My path to hunting started — as many things do — with lunch. My friend Ignacio (“Nazzy”) and I were eating Chinese food made by student chefs in a grudgingly gentrifying part of Vancouver. It was cheap. This was in 2008, during the depths of the Great Recession, when both an economic and environmental apocalypse seemed nigh. Just how nigh was reflected by our conversation, which had drifted to contingency plans for the imminent SHTF (“S**t Hits The Fan,” in survivalist-speak) situation.

“I’d head to Patagonia,” said Nazzy, between bites of General Tao’s chicken, “and live off the land.” He was from Peru, but he would bypass home and keep going to where animals far outnumbered people.

I guess I could have acted less incredulous. “You know how to hunt?” I said. He wiped his mouth with a napkin and sat back from his plate, nodding with an air of gravitas. You have to understand that I’d met Nazzy in business school and though I’ve come to know that he possesses many skills, ranging from ice climbing to tango dancing, he’s just too doe-eyed, compact and cuddly-looking to be a hunter. Or so I thought. Besides, in the almost decade that we’d known each other, I’d never heard him utter a word about hunting.

As it turned out, he’d grown up hunting with his father, a diplomat. Together they’d taken a wide range of fauna on three continents. His father also hunted with a posse of companions whose exploits had become legendary. Now, in their twilight years, they were known more for their doddering misadventures. They’d careen their trucks off the road and blast away with their guns but never hit anything. They were nicknamed after a popular TV show, Los Magnificos, what we in North America would call The A-Team.

By the time coffee came around, Nazzy and I decided that we’d hunt together (Los Magnificos Vancouver Chapter). The ideals of self-reliance and connecting with something primal had gripped us. At the time, DIY food collection and locavorism were on the rise. I must have drunk some of that all-natural Kool Aid. I accepted that I’d been killing things all my life. I’d always eaten meat, and for there to be meat, something needed to have died. Just because I didn’t do the killing myself made me no less complicit. I could see now the sense in David Adams Richards’ idea in Facing the Hunter that “those who eat meat should, at least once in their lifetime, kill that which they eat.”

So we plunged into the acronym-rich bureaucracy necessary to become ticketed hunters in British Columbia. Really, only a couple of weekend-long courses punctuated with multiple-choice exams. First was the P.A.L. (Possession and Acquisition License), needed to purchase and pack heat. Next came the C.O.R.E. (Conservation Outdoor Recreation Education). We needed this for a B.C. Resident Hunter Number, with which we could buy our hunting licenses and species tags. Later, we entered a draw for an L.E.H. (Limited Entry Hunt), a lottery for doe tags, which would improve our chances of harvesting a deer. At this point we were legally entitled to hunt. But all this didn’t make me a hunter any more than C.P.R. certification made me a doctor. Fact is, I still didn’t have the slightest clue where to start.

I had butted up against the biggest hurdle that a newbie hunter faces: the business of how to hunt. It is, one could say, a natural act. But even a baby tiger needs to be taught how to catch its prey. And we urbanite humans, whose Kibble comes neatly packaged, have lost the skill involved in hunting for our food.

My father hadn’t hunted and neither had his. The intergenerational passing of hunting knowledge is ideal, but if that link is broken you have to get it where you can.

Nazzy, though lacking in local knowledge, was well versed in hunting’s first principles. However, despite several scouting trips, we got skunked that first season. To improve our odds for season two, I immersed myself in hunting culture. I went goose hunting with Moose Cree in James Bay, caribou and seal hunting with Inuit in northern Labrador. I perused soft-core “horn porn” — hunting magazines — for the purposes of “positive visualization”; and made myself unpopular by going into hunting stores and asking customers where they hunted. Nazzy, meanwhile, made solo reconnaissance missions to hunting areas within striking distance of Vancouver.

We entered that second season full of hope. We set up camp in the area we had scouted the year before. Whenever possible we stopped to trade information with our camo-clad colleagues, whom Nazzy would jokingly refer to as “less evolved humans.” (Yes, there’s snobbery even within the hunting ranks.) It was a point of pride for him that we didn’t wear a stitch of camouflage. Instead, Nazzy affected a 50s outdoorsman look, with lots of earth-tone wool and retro headgear, that these days is more Gastown hipster than Field & Stream. He played old-time show tunes in his Landcruiser as we rolled through the predawn dark before setting off into the forest. Even with points for style, we weren’t having much luck.

The next day I got that first spike buck muley and learned firsthand what it means to take another mammal’s life. It would be a full two days before I stopped feeling terrible. On the drive home, Nazzy parsed my emotions for me, separating the feeling of sadness from the shame. The shame was pure socialization, something that had been inculcated into my subconscious from my childhood, when I watched the stereotyped hunter kill Bambi’s parents. In any culture in which hunting was a natural part, this emotion would have been as inexplicable as if I’d felt shame over buying my first car.

But before I had the luxury of analyzing these unexpected feelings, we still needed to field dress and butcher the animal. Being apartment dwellers with nowhere to hang the carcass, we had to butcher it into manageable sections right there. We both dragged the deer to the roadside by its hind legs. Nazzy retrieved from the truck a book he’d brought (Dressing & Cooking Wild Game: From Field to Table). While he read out step-by-step instructions, I cut. As we worked, four less evolved humans drove up and leaned out the window to chat. Nazzy hurriedly hid the book. They hadn’t had any luck. We concluded the conversation with a comment that our deer was small, to which one of them responded, “Well, it’s meat, eh.”

Three hours from when we started, an hour and a half from when we got the deer hung, we were finished. I said my last thank you and we left the hooves, spine, ribcage, head and cape in the brush beside the road for the birds and scavengers.

Why did I feel the need to do this? A good question, but more telling is why I still do it, again and again. I now live in an area—Haida Gwaii— where the hunting season is nine months long. Since that first deer, I’ve knelt next to a dozen more, along with a handful of grouse and geese. What exactly is it that I enjoy about hunting? “Enjoy” is not quite the right word. I find it satisfying and rewarding.

First, there are the places that we go in search of game. Places that we otherwise would have no reason to visit. The estuaries, the forested slopes, the fog-bound marshes studded with Tim Burtonesque trees. Even the clearcuts, piled with slash or scrubby young second-growth, have something to offer, if only a small stand of old-growth spared from the saw, or the distinctive water-drop call of a raven we’ve come to know in the area. An owl glides past as the moon comes up, or the first frog of the season chirrups out in the bog.

Hunting on foot is neither easy nor efficient and certainly not always fruitful. But every trip out has yielded some sort of reward, even if it’s simply the time spent outdoors, being out for a sunrise or a sunset, or if we’re lucky bumping into some “adventure,” even one with only a lower-case “a.”

I say “we,” since more often than not I’m hunting with others. And that would be the second thing that I appreciate most, the time that I get to spend with friends in a shared purpose. I feel especially lucky to have introduced a handful of friends to their first hunting experiences.

Then, of course, there’s the meat, the ultimate in organic that I’ve worked hard to procure. As different from store-bought meat as a bleached out tomato bought in a supermarket compared to the rich globe pulled off a vine in your backyard. It’s a special feeling to feed yourself and others with what you’ve hunted and gathered.

I’m proud of how I hunt. However, my initial reaction after dropping an animal is still sadness. I still don’t like the killing part. I have passed on as many animals as I’ve killed, even with my sights set squarely on them. This may sound contradictory, but that’s the way it is. I feel a twang of remorse amid the elation of success each time I’ve taken an animal’s life, and I’ve been told that feeling persists in even veteran hunters. But then I wouldn’t have it any other way.